As I quickly entered the room, the patient, a male in his mid-30’s, was seizing uncontrollably on a gurney. It was a chaotic scene with a host of medical personnel working feverishly in vain attempts to treat and comfort him. The patient was not bleeding. He had no apparent trauma. Other than his seizures, he appeared to be very healthy.

As I quickly entered the room, the patient, a male in his mid-30’s, was seizing uncontrollably on a gurney. It was a chaotic scene with a host of medical personnel working feverishly in vain attempts to treat and comfort him. The patient was not bleeding. He had no apparent trauma. Other than his seizures, he appeared to be very healthy.

I was a young pharmacist responding to the code blue alarm that was triggered moments earlier. Within seconds of my arrival, the patient was quickly whisked away. I saw him for only a few seconds…and never saw him again. After leaving our facility, we learned that he quickly fell into a coma and died later that day.

While this tragic incident occurred over 30 years ago, I’ll never forget it. More importantly, I’ll never forget what caused it.

As is always the case, the culture was created by the leader. What is also always the case, this culture of fear was a breeding ground for a very bad decision.

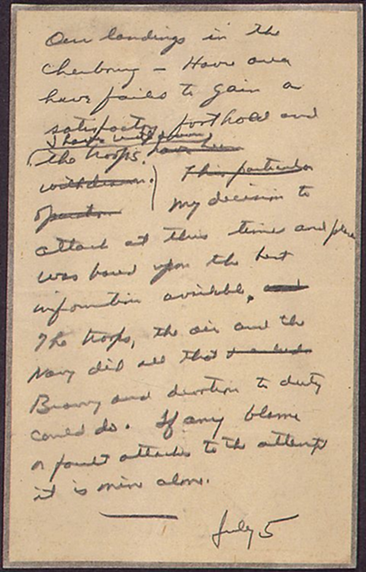

We later discovered that the patient had presented to our urgent care center complaining of chest pain. The medical team correctly diagnosed that he was having a heart attack. The lead physician decided to administer 100mg of lidocaine intravenously – a prudent decision given the situation. The lidocaine was administered by the lead physician. Within seconds of the medication being given, the patient suddenly began to seize uncontrollably. This was the frenzied scene I witnessed when I entered the room.

What happened?

The lead physician made a tragic error. He injected 1000mg of lidocaine instead of 100mg – the patient was mistakenly given 10 times the correct dose. The massive amount of lidocaine erroneously injected into his body caused the seizures, and his demise.

The real cause of this tragic story was something else altogether. Something that every leader – whether working in healthcare, banking, professional sports, a church, any organization – needs to recognize. A culture of fear is a breeding ground for bad decisions.

During the investigation of this catastrophe, it was discovered that one medical professional who was at the bedside recognized at the time that the physician was injecting the wrong dose of lidocaine. However, as astounding as it sounds, he chose not speak up. A disastrous and, in this case, deadly decision. When asked why he remained silent, he stated that he was afraid.  He was afraid because the lead physician had a well-deserved reputation for belittling and humiliating others when questioned.

He was afraid because the lead physician had a well-deserved reputation for belittling and humiliating others when questioned.

What really happened? In the very short period of time – a matter of minutes – when this patient was receiving treatment by this small medical team, the team was working in a culture of fear. As is always the case, the culture was created by the leader. What is also always the case, this culture of fear was a breeding ground for a very bad decision.

If this team had been led by another physician – one who was humble, respectful and welcomed feedback – another culture would have been created. A culture of trust.  If this physician were about to inject this patient with a deadly dose of lidocaine, there is little doubt that the medical professional at the bedside would have made a different decision. He would have spoken up, and this heartbreaking story would have had a much different ending.

If this physician were about to inject this patient with a deadly dose of lidocaine, there is little doubt that the medical professional at the bedside would have made a different decision. He would have spoken up, and this heartbreaking story would have had a much different ending.

I was reticent to tell this sad story. However, it’s a classic example of the type of catastrophic outcome that can occur when decisions are made in cultures of fear. The ‘leg story’ I tell in my TED talk provides another example of this maxim. While my TED talk story and this tragic story involved small teams, there are similar examples of calamitous events occurring on a much larger scale when fear fogs decision making. Chernobyl. Watergate. The Tenerife air disaster.

While there are countless other examples, common themes emerge among all of them. These common themes are the lessons leaders need to remain mindful of.

What are these lessons?

At all levels of leadership, leaders who drive out fear and fill the void with trust make better decisions. Why? Because when they ask for opinions, they won’t hear what they want to hear – they’ll hear what they need to hear. They’ll hear the truth. Necessary changes can be made with minimal drama. Crisis’ will be dealt with more effectively. When a leader drives out fear and fills the void with trust, decision-making is optimized simply because the leader is much better informed.

The leader…specifically the behaviors of the leader…will either drive out fear and create trust, or create fear. The good news is that the leader has 100% control of their behaviors (it’s the only thing a leader has 100% control of! Check out my March 2017 blog to learn more). Therefore, the leader owns which direction – trust or fear – team culture will take. The leader owns the culture.

What type of behaviors create trust?

Being respectful to your team members is a big one. This is much easier when things are going well – much more difficult when they are not. Your crucible moment will come when you get bad news. React respectfully and bring calm out of the chaos, you’ll create trust. React with anger, or worse, shoot the messenger, you’ll create fear. When bad news comes, take a breath and thank the messenger for providing you with the bad news. Further, ask them to thank whoever broke the news to them. Check out my October 2019 blog to learn more about the importance of this behavior.

Being respectful to your team members is a big one. This is much easier when things are going well – much more difficult when they are not. Your crucible moment will come when you get bad news. React respectfully and bring calm out of the chaos, you’ll create trust. React with anger, or worse, shoot the messenger, you’ll create fear. When bad news comes, take a breath and thank the messenger for providing you with the bad news. Further, ask them to thank whoever broke the news to them. Check out my October 2019 blog to learn more about the importance of this behavior.

Be a great leader. Drive out fear. Create trust. You’ll make better decisions because you’ll be better informed.

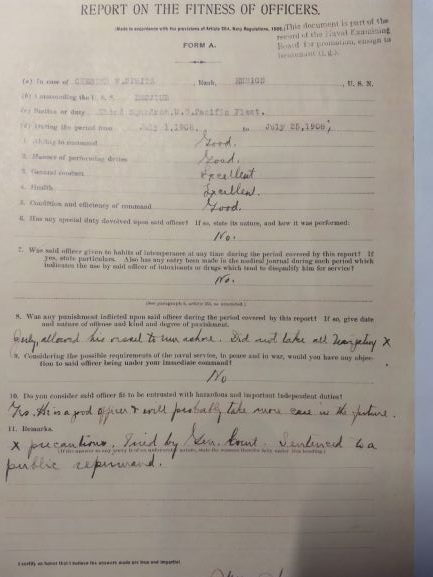

My upcoming book – Lessons from the Navy – which will be published by Rowman and Littlefield in October, discusses many other leadership behaviors that build trust and drive out fear. These behaviors will also be discussed in future blogs and podcasts. Stay tuned!

My upcoming book – Lessons from the Navy – which will be published by Rowman and Littlefield in October, discusses many other leadership behaviors that build trust and drive out fear. These behaviors will also be discussed in future blogs and podcasts. Stay tuned!

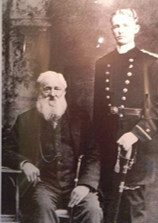

Prior to the epic battle, Nimitz had spent hundreds of hours visiting with his team, calmly and honestly answering questions, asking for and listening to their input, as well as their concerns. As the day of battle approached, Nimitz realized that preparations were complete, orders had been given, and the outcome of the battle was outside his control.

Prior to the epic battle, Nimitz had spent hundreds of hours visiting with his team, calmly and honestly answering questions, asking for and listening to their input, as well as their concerns. As the day of battle approached, Nimitz realized that preparations were complete, orders had been given, and the outcome of the battle was outside his control. He recalled his grandfather’s wise counsel to not worry about things over which he had no control.

He recalled his grandfather’s wise counsel to not worry about things over which he had no control.

I chose the second candidate. Predictably, she did an amazing job, and continues to do tremendous work for our Navy in very high positions of leadership to this day.

I chose the second candidate. Predictably, she did an amazing job, and continues to do tremendous work for our Navy in very high positions of leadership to this day.

You’re disappointed…and angry. Actually…you’re really angry. This was one of your top clients! This mistake cannot be replicated. Your first instinct is to come down hard…make an example…set a precedent. You can certainly rationalize firing him. On the other hand, while new, he’s consistently delivered. Again, you sense he has a lot of potential. What do you do – fire or forgive?

You’re disappointed…and angry. Actually…you’re really angry. This was one of your top clients! This mistake cannot be replicated. Your first instinct is to come down hard…make an example…set a precedent. You can certainly rationalize firing him. On the other hand, while new, he’s consistently delivered. Again, you sense he has a lot of potential. What do you do – fire or forgive?

suddenly make a serious blunder, remember the story of Ensign Nimitz. These are crucible moments for leaders – whether to fire or forgive. Your first instinct will probably be to come down hard…make an example…set a precedent…perhaps fire them. However, be a great leader. Be mindful as you wrestle with the ‘fire or forgive’ dilemna. Take a breath and consider their potential future contributions to the organization.

suddenly make a serious blunder, remember the story of Ensign Nimitz. These are crucible moments for leaders – whether to fire or forgive. Your first instinct will probably be to come down hard…make an example…set a precedent…perhaps fire them. However, be a great leader. Be mindful as you wrestle with the ‘fire or forgive’ dilemna. Take a breath and consider their potential future contributions to the organization. I had the pleasure of giving a leadership presentation at the annual Master Executive Corporate Coach conference earlier this month in beautiful San Diego. I was also able to attend the conference and participate in some fascinating discussion on the topic of leadership with thought leaders from around the world.

I had the pleasure of giving a leadership presentation at the annual Master Executive Corporate Coach conference earlier this month in beautiful San Diego. I was also able to attend the conference and participate in some fascinating discussion on the topic of leadership with thought leaders from around the world. As a leader, you’re guaranteed one thing: adversity will strike. Challenges, issues, and problems are coming your way. Getting bad news and facing adversity is a certainty—it’s not a matter of if, but when. These are crucible moments for a leader. However, while gut-wrenching, they are also moments of tremendous opportunity. Let me explain.

As a leader, you’re guaranteed one thing: adversity will strike. Challenges, issues, and problems are coming your way. Getting bad news and facing adversity is a certainty—it’s not a matter of if, but when. These are crucible moments for a leader. However, while gut-wrenching, they are also moments of tremendous opportunity. Let me explain. If you show anger or, worse yet, shoot the messenger, you’ll lose trust and move team culture toward one of fear. Cultures of fear diminish info sharing, insulate the leader from reality, and breed unwise decisions. Disaster awaits an ill-informed leader.

If you show anger or, worse yet, shoot the messenger, you’ll lose trust and move team culture toward one of fear. Cultures of fear diminish info sharing, insulate the leader from reality, and breed unwise decisions. Disaster awaits an ill-informed leader.

I was surprised and disappointed to learn that they sometimes treated their employees with outright disdain.

I was surprised and disappointed to learn that they sometimes treated their employees with outright disdain.

Knowing all this, no matter how taxing the job – and carving out time to workout became much more challenging during the last 10 years of my career – my commitment to maintain an exercise routine never wavered.

Knowing all this, no matter how taxing the job – and carving out time to workout became much more challenging during the last 10 years of my career – my commitment to maintain an exercise routine never wavered.