You have a new member on your team who has done well during their first few months onboard. He comes to work with a good attitude and has completed all tasks on time. Overall, he’s been a nice addition to your team. Your gut tells you he may be a future high performer.

But then it happened – he blunders. It’s not a minor blunder – it’s serious. Maybe he forgot to follow-up with a major client and you’ve lost their business. It was an honest mistake but an extremely costly one – you lost a top client.

You’re disappointed…and angry. Actually…you’re really angry. This was one of your top clients! This mistake cannot be replicated. Your first instinct is to come down hard…make an example…set a precedent. You can certainly rationalize firing him. On the other hand, while new, he’s consistently delivered. Again, you sense he has a lot of potential. What do you do – fire or forgive?

You’re disappointed…and angry. Actually…you’re really angry. This was one of your top clients! This mistake cannot be replicated. Your first instinct is to come down hard…make an example…set a precedent. You can certainly rationalize firing him. On the other hand, while new, he’s consistently delivered. Again, you sense he has a lot of potential. What do you do – fire or forgive?

Be mindful as you wrestle with the ‘fire or forgive’ dilemna. Take a breath and consider their potential future contributions to the organization.

While researching material for my next leadership book, I’ve come across a fascinating story that provides some insight for leaders facing this exact challenge.

Fleet Admiral Nimitz

My book will tell the story of how a soft-spoken, quiet man led 2 million soldiers and sailors scattered over 60 million square miles – nearly half the world’s surface. It’s the story of leadership behaviors employed by Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz between 1941 and 1945 that won an overwhelming victory over the Empire of Japan in World War II. The behaviors employed by Nimitz are as applicable today as they were in the 1940’s.

Ensign Nimitz

Decades before Nimitz successfully led a naval force whose size, power and complexity dwarfed all maritime campaigning before or since, he committed a serious blunder. In 1908 Ensign Nimitz was Commanding Officer of the old and rusty destroyer USS Decatur. On the dark evening of July 7, 1908, while steaming off the shores of Luzon in the Philippine Islands, Ensign Nimitz committed the unforgivable sin of grounding his naval vessel on a mud bank.

USS Decatur

Grounding a naval vessel is, and always has been, a serious blunder in the US Navy. It’s an infraction that is the fastest way for a Commanding Officer to get fired and begin the process of looking for civilian employment.

Perhaps he saw the future greatness in Nimitz.

However, in this case, Ensign Nimitz was not fired. He was tried by court martial for ‘hazarding a ship’ and sentenced to a ‘public reprimand’. [1]His career was not ended – he was permitted to continue his naval service.

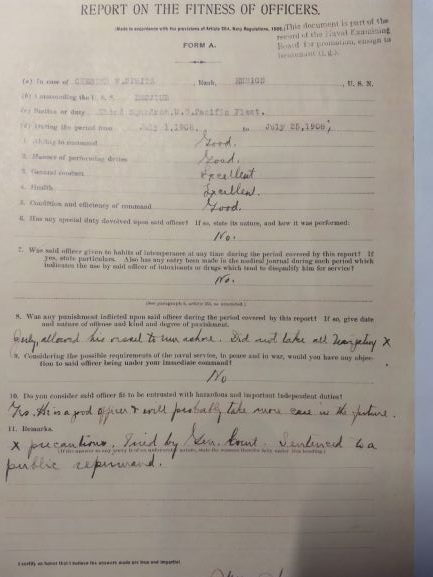

Ensign Nimitz’s Fitness Report circa 1908

During my research I found Ensign Nimitz’s 1908 fitness report (see image on right). The grounding incident is referenced in the evaluation, stating Nimitz “allowed his vessel to run ashore”. In answer to the question, “Do you consider said officer [Nimitz] fit to be entrusted with hazardous and important independent duties?”, Nimitz’s boss wrote, “Yes. He is a good officer and will probably take more care in the future.”

I’ve not been able to identify Nimitz’s boss – the Admiral who penned these words. We’ll probably never know his thoughts as he wrestled with what to do with young Nimitz. Fire or forgive. He probably considered coming down hard…making an example…setting a precedent…and ending Nimitz’s career. In the end, why didn’t he?

Perhaps he saw the future greatness in Nimitz. Clearly Nimitz’s boss – his identity lost to history – made the right decision. Ensign Nimitz would go on to win the most important naval campaign in American history, and arguably one of the most pivotal in human history.

What’s the lesson for today’s leaders? The next time you have a new member of your team – someone who has done well and seems to be a good fit –  suddenly make a serious blunder, remember the story of Ensign Nimitz. These are crucible moments for leaders – whether to fire or forgive. Your first instinct will probably be to come down hard…make an example…set a precedent…perhaps fire them. However, be a great leader. Be mindful as you wrestle with the ‘fire or forgive’ dilemna. Take a breath and consider their potential future contributions to the organization.

suddenly make a serious blunder, remember the story of Ensign Nimitz. These are crucible moments for leaders – whether to fire or forgive. Your first instinct will probably be to come down hard…make an example…set a precedent…perhaps fire them. However, be a great leader. Be mindful as you wrestle with the ‘fire or forgive’ dilemna. Take a breath and consider their potential future contributions to the organization.

[1] Warner, Oliver. Command at Sea. New York: St Martins Press. 1976. 193